Research

- Where do Binary Black Holes Form?

- Black Hole Dynamics

- Massive-Star Evolution

- The Binary-Host Connection

- Synthesizing the Heaviest Elements in the Universe

- Bayesian Statistics

- Citizen Science

Current catalog of gravitational-wave events. Sudarshan Ghonge/Karan Jani

Current catalog of gravitational-wave events. Sudarshan Ghonge/Karan Jani

Throughout the history of astronomy, humanity has been reliant on one form of information to build our knowledge about the cosmos — light. However, in the past few years, astronomers have unlocked a new messenger from the cosmos, a new sense with which to explore the universe. This phenomena, known as gravitational waves, are minuscule ripples in the fabric of spacetime that encode information about objects with extreme gravity in the universe, such as black holes and neutron stars. I am part of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which since 2015 has observed gravitational waves from nearly 100 merging compact objects in the universe. My research focuses on using gravitational waves and other high-energy astrophysical phenomena to learn about the formation, lives, and deaths of massive stars.

Where do Binary Black Holes Form?

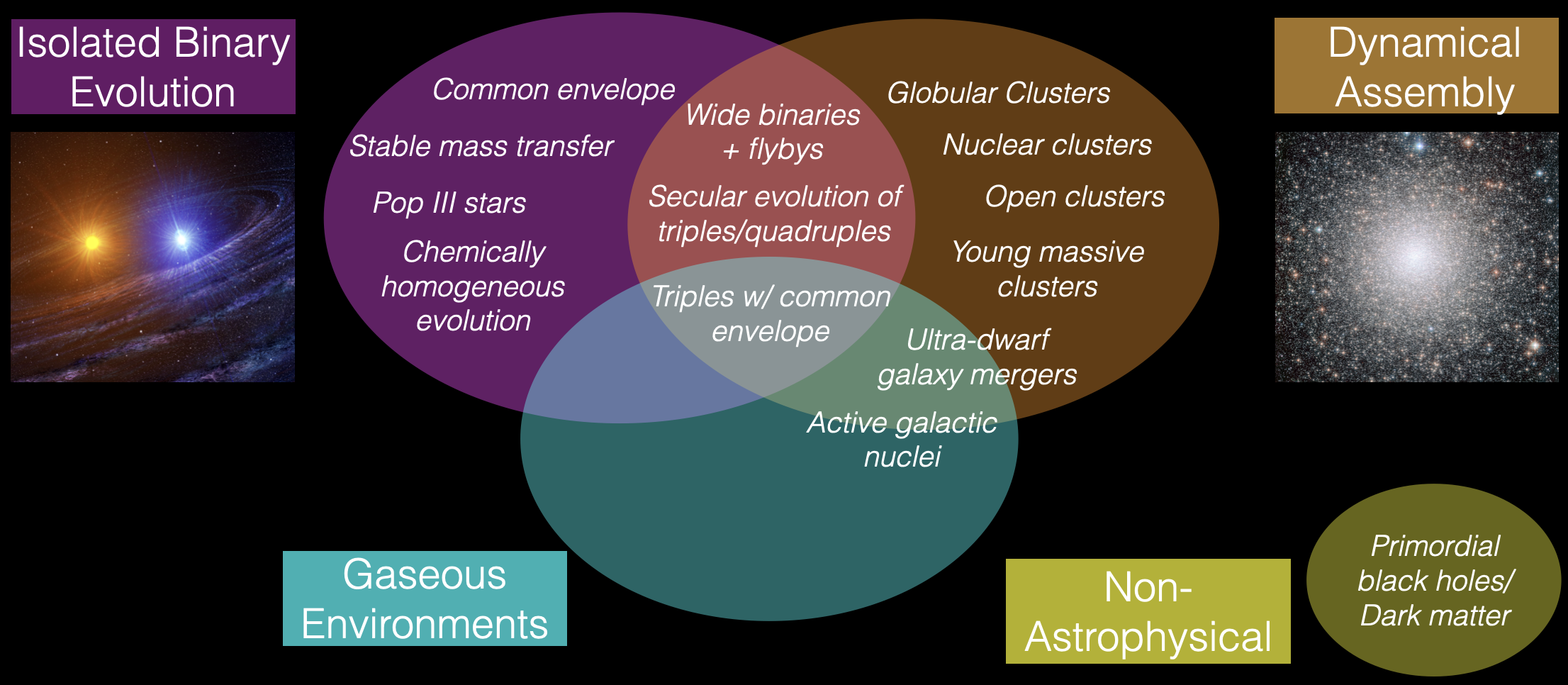

Black holes and neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars. Therefore, detecting these dark objects in gravitational waves offers a menas for understanding the lives of their progenitors, such as the environments they were born in, the complicated evolutionary processes that persisted throughout their lives, and the supernovae that marked their deaths. To complicate matters, there are multiple pathways that astronomers believe may lead to merging compact objects, such as through the evolution of two massive stars in isolation or through dynamical encounters of black holes in dense stellar systems such as globular clusters. These pathways predict different properties for the merging black holes, such as masses, spins, and orbital eccentricities, which are encrypted in the gravitational wave signals we detect. I work to build statistical models which combine the growing observational sample of gravitational waves with detailed simulations of compact binary formation, providing insights into the relative efficiency of various formation channels and constraining uncertain physical aspects of stellar evolution.

Proposed formation environments of gravitational-wave sources.

Proposed formation environments of gravitational-wave sources.

Related Publications:

- Constraining Formation Models of Binary Black Holes with Gravitational-wave Observations

- One Channel to Rule Them All? Constraining the Origins of Binary Black Holes using Multiple Formation Pathways

Black Hole Dynamics

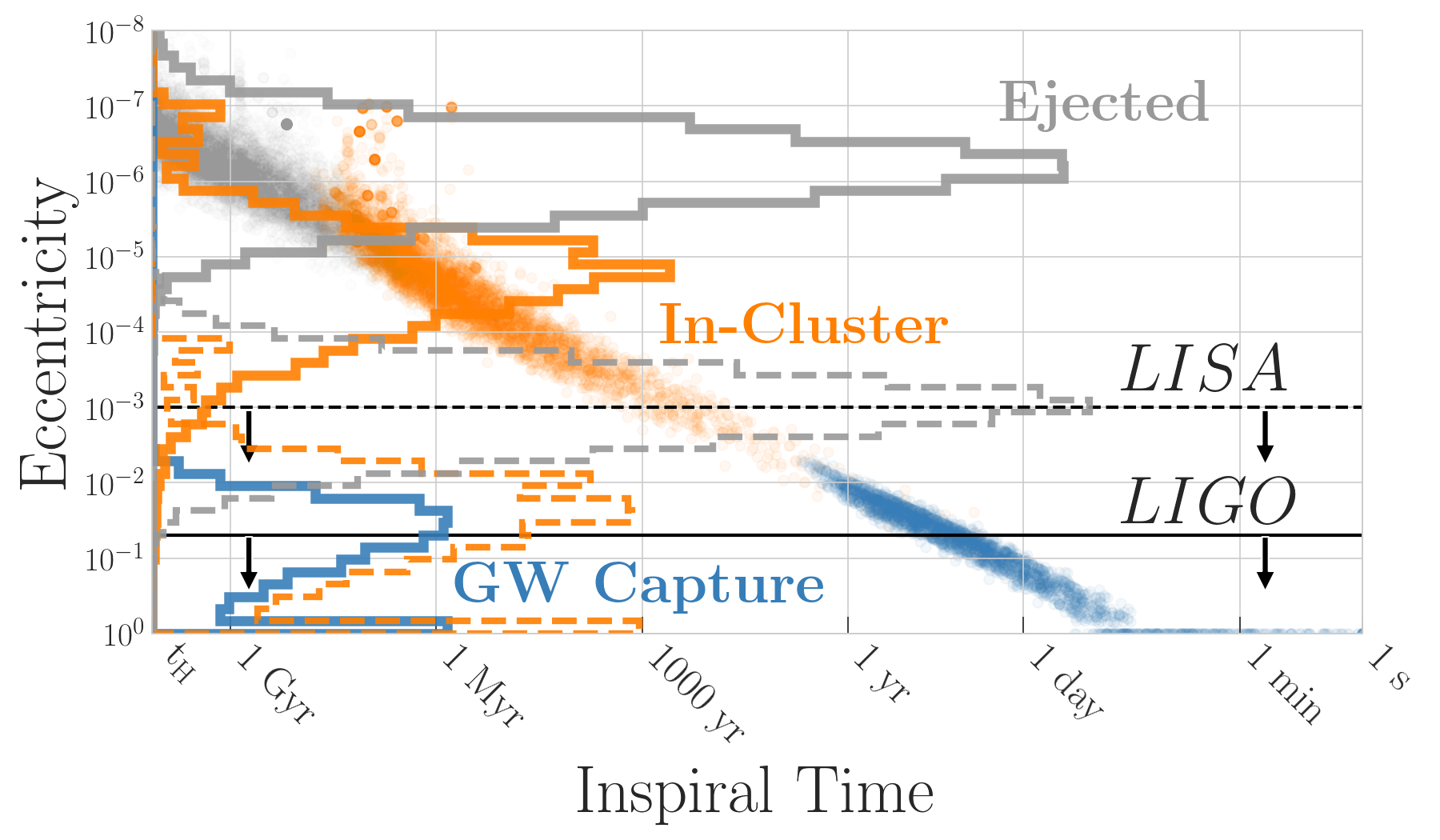

In dense stellar environments such as globular clusters, black holes sink into the cluster cores where stellar densities can be a million times higher than the stellar densities of our galactic neighborhood. This leads to strong gravitational encounters between black holes, which can dynamically assemble new binaries that will merge through gravitational-wave emission. Oftentimes, these dynamical dances can impart large eccentricities into the newly-formed black hole binaries, which can expedite their merger and will be a key distinguishing signature in the gravitational-wave data. I am interested in modeling such encounters (see simulations here), and understanding how eccentric detections can determine the efficiency of dynnamical channels in synthesizing black hole binaries.

Expected eccentricity distribution for black hole mergers in globular clusters. Adapted from Zevin et al. 2019a.

Expected eccentricity distribution for black hole mergers in globular clusters. Adapted from Zevin et al. 2019a.

Related Publications:

- Eccentric Black Hole Mergers in Dense Star Clusters: The Role of Binary-Binary Encounters

- Implications of Eccentric Observations on Binary Black Hole Formation Channels

- Avoiding a Cluster Catastrophe: Retention Efficiency and the Binary Black Hole Mass Spectrum

Massive-Star Evolution

Many aspects of massive-star evolution are highly uncertain, and this uncertainty becomes even worse when dealing with stars that are in binary systems (which most massive stars are). To constrain these physical uncertainties, we can turn to population synthesis, where we can rapidly simulate large populations of systems such as binary black holes and binary neutron stars using various physical assumptions. These populations can then be compared with the observation sample of systems detected with gravitational waves or other means. I have worked to help develop a population synthesis code called COSMIC, which is completely open source and version controlled. I’ve used this code to investigate some of the most exceptional gravitational-wave events to date, such as the merger of a black hole with a compact object that lies in the regime between known black holes and neutron stars.

Artist’s illustration of an interacting massive-star binary. Systems like these can result in neutron stars and black holes that merge as gravitational-wave sources.Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser/S.E. de Mink.

Artist’s illustration of an interacting massive-star binary. Systems like these can result in neutron stars and black holes that merge as gravitational-wave sources.Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser/S.E. de Mink.

Related Publications:

- Exploring the Lower Mass Gap and Unequal Mass Regime in Compact Binary Evolution

- Suspicious Siblings: The Distribution of Mass and Spin across Component Black Holes in Isolated Binary Evolution

The Binary-Host Connection

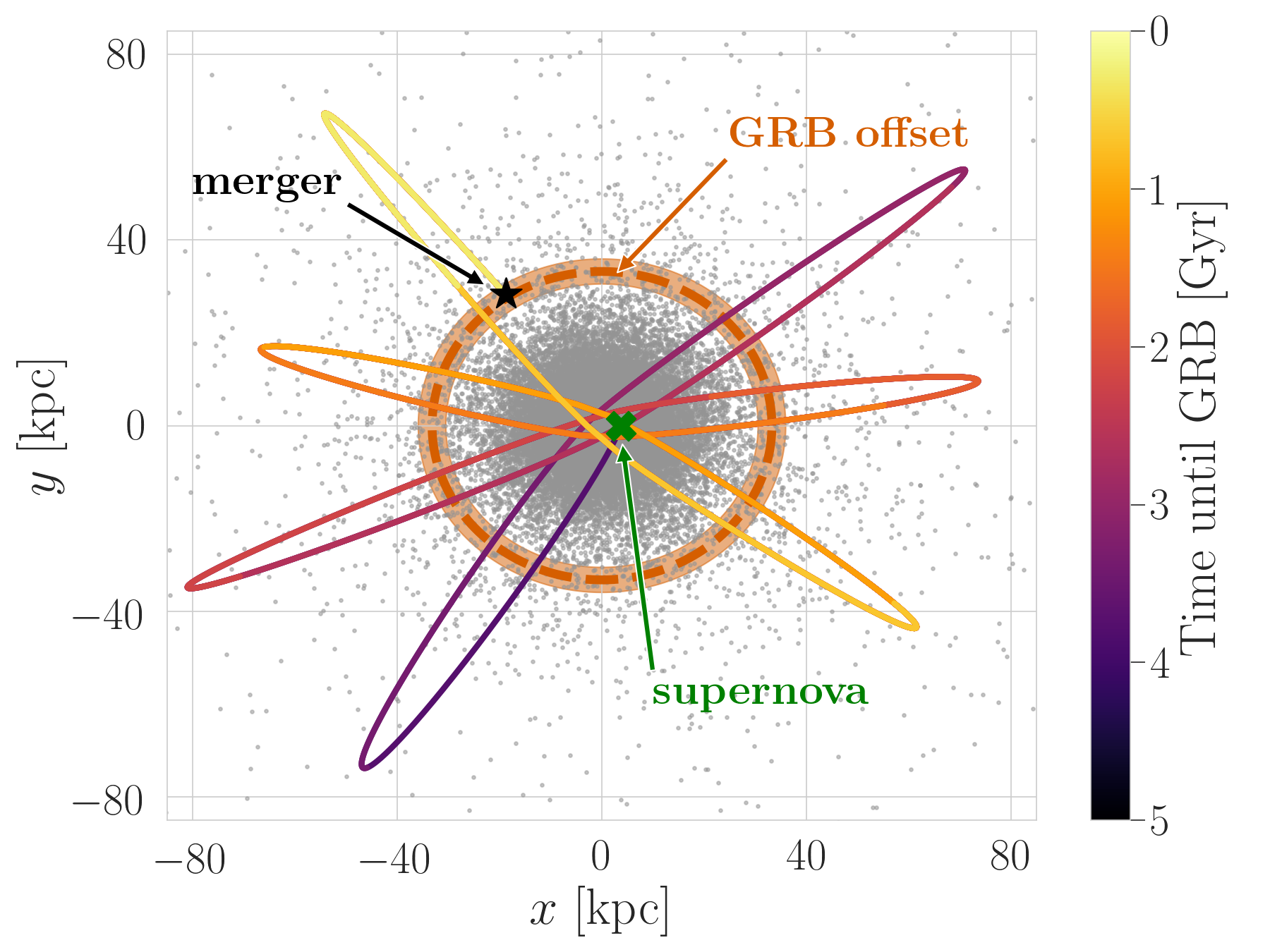

Ground-based gravitational wave detectors can also detect the merger of the dense remnant cores of massive stars, known as neutron stars. The first detection of merging neutron stars in August 2017 and was accompanied by a rainbow of light across the entire electromagnetic spectrum from the subsequent kilonova explosion and gamma-ray burst. This discovery was the first to combine gravitational waves and light to build a better understanding of an astrophysical event - the “holy grail” of multi-messenger astronomy. I also study how we can use such detections, as well as detections of other high-energy transients such as short gamma-ray bursts, to extrapolate backwards in time and learn about the stellar system that formed the neutron stars and the evolution of their galactic hosts. The supernovae that form neutron stars also lead to a great migration, oftentimes flinging the system to the outskirts of its galactic host. The location of the merger relative to the host galaxy can therefore illuminate uncertain aspects of supernova physics.

Potential kinematic evolution of a binary neutron star progenitor to a short gamma-ray burst that is highly offset from its host galaxy. Adapted from Zevin et al. 2020c.

Potential kinematic evolution of a binary neutron star progenitor to a short gamma-ray burst that is highly offset from its host galaxy. Adapted from Zevin et al. 2020c.

Related Publications:

- On the Progenitor of Binary Neutron Star Merger GW170817

- Forward Modeling of Double Neutron Stars: Insights from Highly-Offset Short Gamma-Ray Bursts

- Observational Inference on the Delay Time Distribution of Short Gamma-Ray Bursts

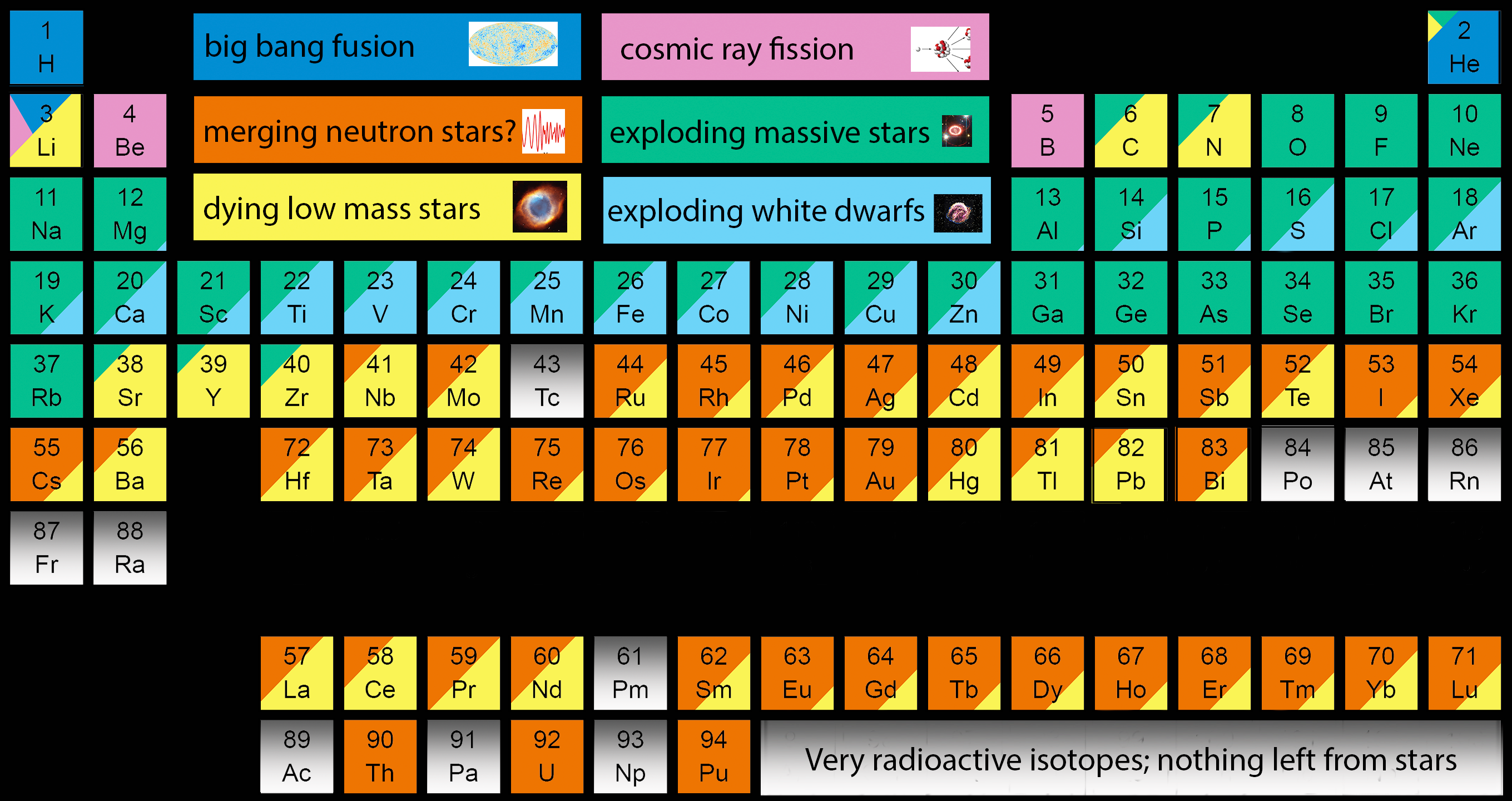

Synthesizing the Heaviest Elements in the Universe

When neutron stars merge, they enrich the cosmos with some of the heaviest elements in the Universe, such as gold and platinum. Looking at the abundance of these “r-process” elements in different galactic environments can therefore tell us where and when neutron stars were merging. I study how observations of r-process enriched stars in galactic environments such as such as globular clusters and ultra-faint dwarf galaxies can help decipher aspects of massive binary star evolution and neutron star formation.

Astrophysical origin of elements. Merging neutron stars (orange) are how many of the heaviest elements on the periodic table form. Credit: Jennifer Johnson/Ohio State University.

Astrophysical origin of elements. Merging neutron stars (orange) are how many of the heaviest elements on the periodic table form. Credit: Jennifer Johnson/Ohio State University.

Related Publications:

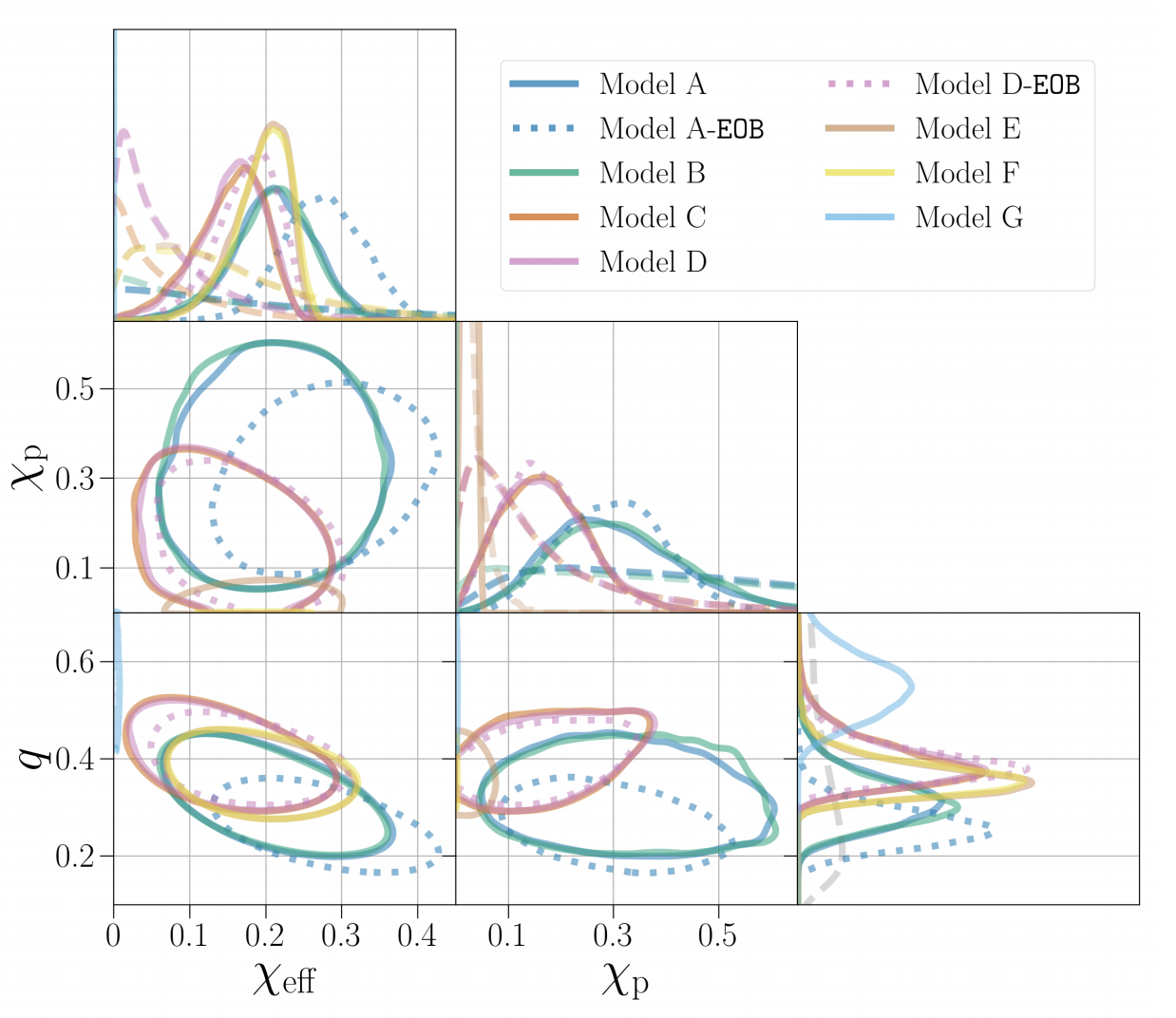

Bayesian Statistics

The properties of compact binaries detected via gravitational waves, such as their masses, spins, and redshifts, are determined through Bayesian parameter estimation. In some cases, the inferred values of such parameters can change when different Bayesian priors are assumed, which account for one’s prior belief in a particular problem. I’m interested in investigating the robustness of parameter estimates to differing prior assumptions, particularly astrophysically-motivated and population-based priors. For example, by performing analyses with different prior assumptions, we found that the first measurement of non-zero component spin in a binary black hole merger can robustly be attributed to the larger of the two black holes in the merger.

Influence of Bayesian priors on inferred mass and spin parameters of gravitational-wave event GW190412. From Zevin et al. 2020b.

Influence of Bayesian priors on inferred mass and spin parameters of gravitational-wave event GW190412. From Zevin et al. 2020b.

Related Publications:

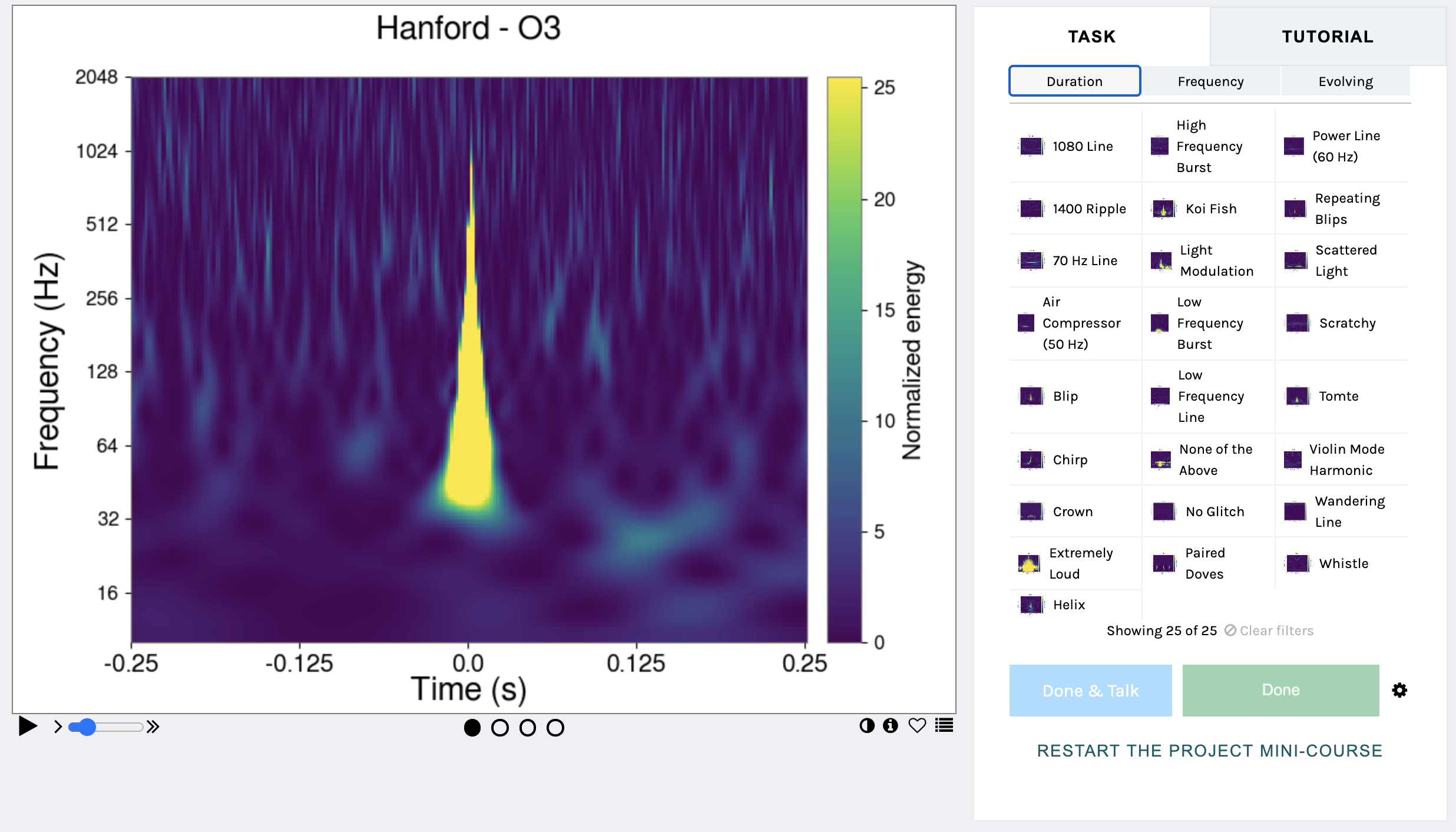

Citizen Science

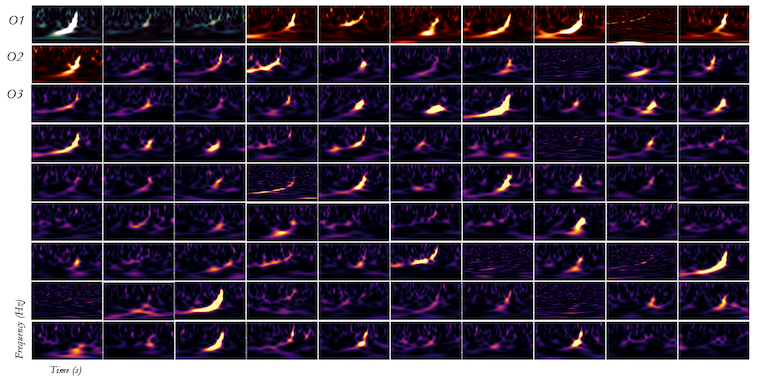

One other area of research I am involved in is “citizen science” — involving the general public scientific data analysis through crowdsouring. I helped to build the first gravitational-wave project on the Zooniverse citizen science platform: Gravity Spy. Being the most sensitive gravtitaional experiment ever built, the LIGO detectors are susceptible to sources of environmental and instrumental noise, known as “glitches”, which afflict our sensitivity to the gravitational-wave universe and can even masquerade as astrophysical signals. A comprehensive characterization of such noise signals is paramount to the LIGO and Virgo detectors achieving their sensitivity goals. However, as hundreds of thousands of glitches occur in the detectors during an observing run, this task would overwhelm any small group of scientists. The Gravity Spy project combines the power of machine learning algorithms withs volunteers from the general public to look at gravitational-wave data containing glitches, and better understand where such sources of noise come from. This project has been highly successful, with over 3.8 million classifications from over 22,500 registered users to date. Creating a symbiotic relationship between volunteer classifications and machine learning will help to scale citizen science with the ever-increasing datasets of the future.

The Gravity Spy classification task.

The Gravity Spy classification task.

Related Publications: